Understanding the Maia: Dissecting Angels of Middle-earth

Looking at the angelic forebeings--using Tolkien's own words--in relation to the cosmic structure of powers.

If you’ve ever read The Silmarillion (or any Tolkien literature that referenced them) and felt like the word “Maiar” got tossed into the air like confetti—don’t worry. Tolkien does that. He assumes you’ll either keep up, or at the very least you’ll go back and re-read it like a monk copying manuscripts. I jest, but in all honesty the term Maiar (plural of “Maia”) takes the reader through many, oftentimes disjointed, tunnels of descriptions and questions of organizational structure. And while I want this article to focus on the Maia, we’re going to have to reference the entire cosmic structure of Middle-earth, which is daunting to say the least. We can make sense of it, though.

The best introduction—and definition across all of Tolkien’s works—of the Maiar is found in The Silmarillion, in the chapter titled “Valaquenta: Account of the Valar and Maiar according to the lore of the Eldar”:

“With the Valar came other spirits whose being also began before the World, of the same order as the Valar but of less degree. These are the Maiar, the people of the Valar, and their servants and helpers. Their number is not known to the Elves, and few have names in any of the tongues of the Children of Ilúvatar; for though it is otherwise in Aman, in Middle-earth the Maiar have seldom appeared in form visible to Elves and Men.”1

So, in Tolkien’s own terms, a Maia is:

a spiritual being

of the same “order” as the Valar (but lesser)

those who entered the world at its beginning

often serving one of the great Powers.

If we really wanted to synthesize the Maiar, we could say they’re angelic beings—servants of the “gods”—who can take physical form and interact with the world. That, of course, misses the rich depth of their being. Still, we can formulate a general idea as to what they are, in the organizational structure of the cosmic powers. The Valar are like archangels (or “powers”), and the Maiar are like angels who serve them. I’m immediately comparing this to Gabriel and Michael, the biblical archangels, who hold power over legions of angels under them. Clearly, there’s a structure to this all.

Tolkien proceeds to introduce some Maiar by name (or type), and this will be the best way for us to directly understand the Maiar’s working in the affairs of Middle-earth. But, since most take the form of “wizard”, let’s define the wizards before we get any further. As explained in The Silmarillion:

“…there appeared in the west of Middle-earth the Istari, whom Men called the Wizards. None knew [whence they were], save Círdan… and only to Elrond and to Galadriel did he reveal they came over the Sea. But afterwards it was said among the Elves that they were messengers sent by the Lords of the West to contest the power of Sauron…to move Elves and Men and all things of good will to valiant deeds. In the likeness of Men they appeared, old but vigorous, and they changed little with the years, and aged but slowly, though great cares lay on them; great wisdom they had, and many powers of mind and hand. Long they journeyed far and wide among Elves and Men, and held converse also with beasts and with birds; and the peoples of Middle-earth gave to them many names…”2

It challenges any preconceived notion we might have of a “wizard”. Transparently—having entered the Tolkien gateway through the Jackson films as a child—it shocked me to later learn there was an entire universe of lore that added immeasurable depth to what I thought was a fascinating, powerful, magic-wielding old man, in Gandalf. And so, it’s two of the Istari—the Maiar-wizards—with whom we need to familiarize ourselves, along with a “Dark Lord”, and of course a fiery beast.

Oh, and one more tip: If you’re a little overwhelmed here, let’s take a pause to consider the power struggle here, or more fitting, the angelic/gods’ organizational structure:

Ilúvatar is the one, most powerful and originator God.

Ainur are the primordial spirits created by Ilúvatar, and they include both good and evil beings

Valar are a subset of Ainur who chose to enter Middle-earth and become the powers of Arda. The difference between Valar and Ainur is whether or not they enter Arda (the world).

Enter = Valar

Stay with Ilúvatar in the cosmos = Ainur

Hopefully that helps. Let’s dig in.

Sauron

We can’t dissect the topic of Maiar without starting with Sauron. According to The Silmarillion:

“Among those of his servants that have names the greatest was that spirit whom the Eldar called Sauron, or Gorthaur the Cruel. In his beginning he was a Maiar of Aulë; he remained mighty in the lore of that people. In all the deeds of Melkor the Morgoth upon Arda, in his vast works and in the deceits of his cunning, Sauron had a part, and was only less evil than his master in that for long he served another and not himself. But in after years he rose like a shadow of Morgoth and a ghost of his malice, and walked behind him on the same ruinous path down into the Void.

That description explains why Sauron is so obsessed with order, craft, making, building, systems; domination through design. He served the Valar Aulë, who is described as follows: “He is a smith and a master of all crafts, and he delights in works of skill…”3 Essentially, he is a corrupted craftsman. Much like Lucifer in Scripture, Sauron didn’t began as evil, rather, he fell into evil. However, unlike Scripture and Lucifer being authoritative over evil and sin, Sauron served the rebel Valar Melkor. Sauron is the most tangible of the evil forces (for us) in Middle-earth, because he became Melkor’s agent and chief lieutenant in the War of the Ring.

And while we, the readers (or film viewers) perceive Sauron as ultimately powerful in spirit, we have to understand that organizationally, he doesn’t necessarily stand apart from the other Maia, although he is the most powerful. In his might, he is able to corrupt other Maiar, which takes us to our next fallen being:

Saruman

Curunír was one of the Maiar sent to Middle-earth at the request of Manwë; five emissaries were to go to Middle-earth and protect the free people from the shadow of Sauron, who’d been defeated yet not entirely destroyed. Curunír, who was known as Saruman to the inhabitants of Middle-earth, was the wisest of them all.

With the growing threat of Sauron’s influence at the behest of Melkor, the Lady Galadriel established an oversight organization of Istari and elves. Thus the “White Council” was formed and comprised of Saruman, Gandalf, Radagast, Círdan, Elrond and Galadriel. Saruman inhabited Orthanc, where he discovered a palantir, in which the spirit of Sauron was able to infiltrate his already-independent and contrarian mind. It was a quick and dangerous corruption.

We see in Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth:

“'Who would go? For they must be mighty, peers of Sauron, but must forgo might, and clothe themselves in flesh so as to treat on equality and win the trust of Elves and Men. But this would imperil them, dimming their wisdom and knowledge, and confusing them with fears, cares, and wearinesses coming from the flesh.' But two only came forward: Curumo [Curunír], who was chosen by Aulë, and Alatar, who was sent by Orome.”4

This “choosing” is important, because we know Sauron was chosen by Aulë, too. Their similarities are not coincidence. Both had minds of industrialization, domination, and control by sheer power. Saruman didn’t fall because he’s weak. He fell because he starts to believe power is the only way to fight power.

He was sent to oppose Sauron, but he becomes a smaller, uglier version of him. Yet, another Istari was sent, as well—one we know and love.

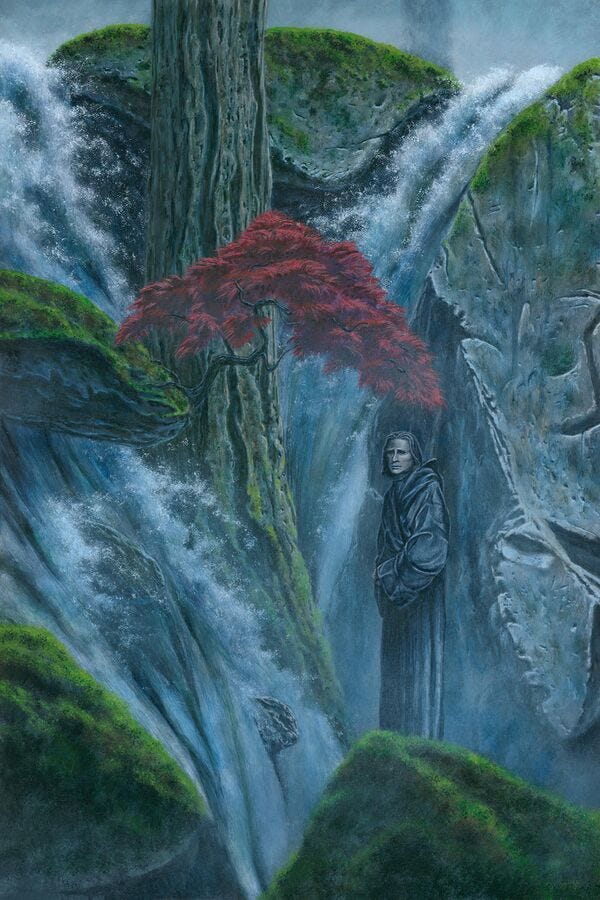

Gandalf

Olórin, known to Middle-earth as Gandalf, was sent with Saruman, and started their servitude similarly.

“Wisest of the Maiar was Olórin. He too dwelt in Lórien, but his ways took him often to the house of Nienna, and of her he learned pity and patience. Of Melian much is told in the Quenta Silmarillion. But of Olórin that tale does not speak; for though he loved the Elves, he walked among them unseen, or in form as one of them, and they did not know whence came the fair visions or the promptings of wisdom that he put into their hearts. In later days he was the friend of all the Children of Ilúvatar, and took pity on their sorrows; and those who listened to him awoke from despair and put away the imaginations of darkness.”5

As aforementioned, it’s one thing to see Gandalf as an old, sword-and-staff fighting wizard. And that’s cool. But the deeper level of him being a Maiar? That changes everything. It’s why he declines the Ring when it’s offered to him by Frodo, as well. His power has to be in check—he’s forbidden to use his full power against Sauron as it is. That power enhanced by the Ring? Absolutely not. This also further explains how he’s able to defeat the thing that temporarily defeated him in the mines of Moria.

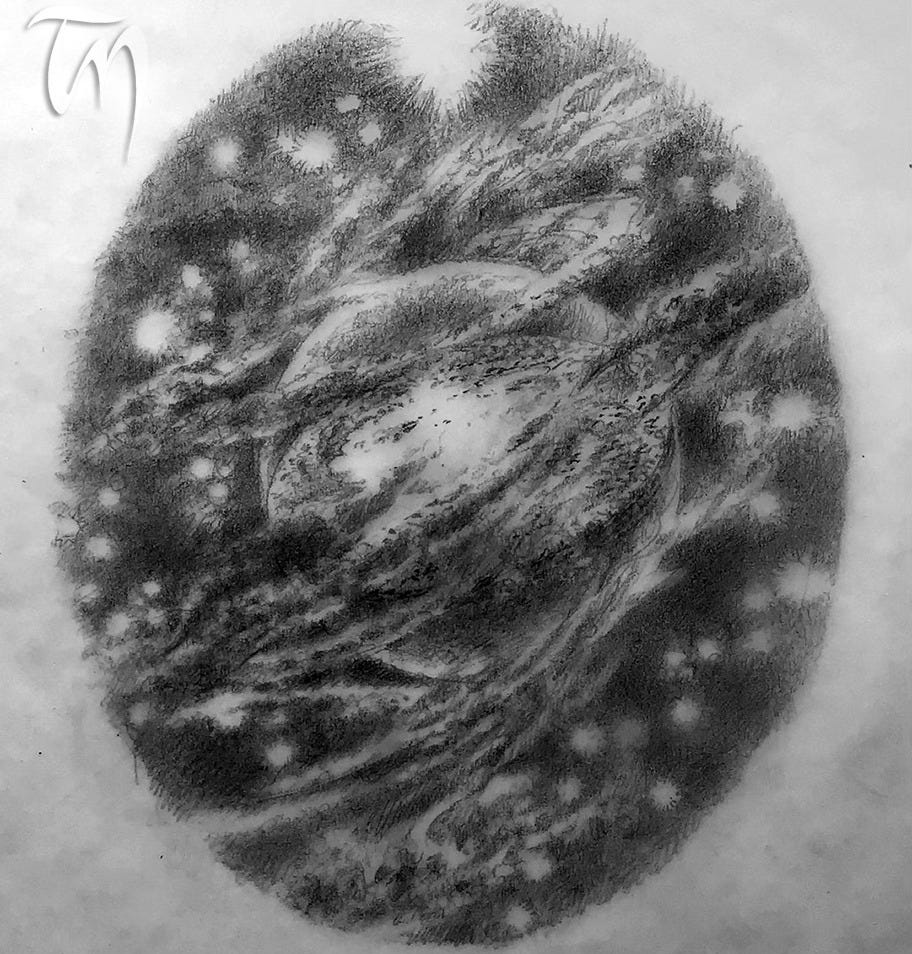

Balrogs

Like the rest, there’s more to the surface in Middle-earth than meets the eye. The Balrog the fellowship encounters isn’t just another enemy in their path: it’s a demon. It’s a fallen Maia.

“Dreadful among these spirits were the Valaraukar, the scourges of fire that in Middle-earth were called the Balrogs, demons of terror.”6

Notice that—plural! If you haven’t read The Silmarillion that may come as a shock to you. But there are multiple Balrogs, and they are fallen Maiar that were corrupted by Melkor during creation.

Tolkien provided additional context in a letter to a Naomi Mitchison in 1954:

“The Balrog is a survivor from the Silmarillion and the legends of the First Age. The Balrogs, of whom the whips were the chief weapons, were primeval spirits of destroying fire, chief servants of the primeval Dark Power of the First Age. They were supposed to have been all destroyed in the overthrow of Thangorodrim, his fortress in the North. But it is here found (there is usually a hang-over especially of evil from one age to another) that one had escaped and taken refuge under the mountains of Hithaeglin (the Misty Mountains). It is observable that only the Elf knows what the thing is – and doubtless Gandalf.”7

And so, while we don’t know which Maia were corrupted to become Balrogs, we at least get a simple reality that Balrogs are indeed Maia, and that is why Gandalf had such a tough time fighting, and defeating (while being temporarily defeated himself) it in the mines of Moria.

I hope you have a better understanding of Maia! Or at least, I hope I didn’t further confuse you. Like our own physical-spiritual world, the Maiar are Tolkien’s reminder that Middle-earth isn’t merely a stage for kings and warriors—any fantasy novel can provide that. Instead, Middle-earth is a battleground for the unseen. The Wizard is not simply a wizard; the Dark Lord is not merely a tyrant; even the Balrog is not some ferocious beast. For Tolkien, the spiritual world presses down into the physical, and the physical world bears the weight of the spiritual. The Maiar are where those two realms touch.

A Personal Update

Thanks for taking this journey with me! As many of you know, my wife and I are welcoming our son into the world THIS MONTH! She’s scheduled for a c-section on February 20th (if the little man holds on that long) and we covet your prayers. That said, I’m unsure how much content I’ll be able to provide over the next 4-5 weeks. Stay with me during the brief hiatus. I’ve got lots of ideas rolling around that I’ll publish in very short order. Until then, please consider subscribing—free or paid (babies are expensive, I’m learning).

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Silmarillion. Edited by Christopher Tolkien, 2nd ed., Harper Collins, 1999. 18.

Ibid., 334.

Ibid., 13.

Tolkien, J. R. R. Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth. Edited by Christopher Tolkien, HarperCollins, 2006. 393.

Ibid., 20.

Ibid.

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Edited by Humphrey Carpenter, with the assistance of Christopher Tolkien, Houghton Mifflin, 1981. Letter 144.

Thanks for this, great breakdown!! If you ever wanted to // could do a Part II, would love to hear your thoughts of main Maiar like Melian, Ossë, Melian, Uinen, Tilion, and Arien 🙏🏻 and my best, congratulations on your forthcoming bundle of joy!!

This is a good summary. I especially like Tolkien’s insistence that the job of the Istari is to encourage and advise rather than dominate.