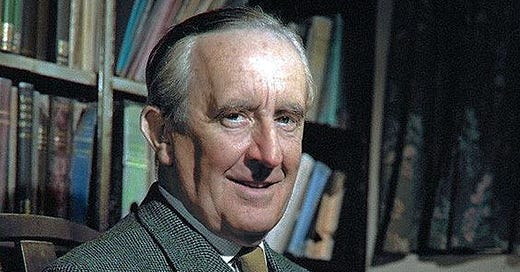

Tolkien's Middle-earth as a Gateway to Christianity

Thoughts on J.R.R. Tolkien's legendarium as a path to God

I had a recent encounter with an individual, well-intended as they might be, who claimed that J.R.R. Tolkien wasted his life, that it could’ve been better spent had he not “rambled about fantasy lands and preached the Gospel instead”—and at face value, there may be some truth in that sentiment. After all, someone so gifted in writing—prose and philology, a technical obsession with words—could have certainly been counted among the all-time great Christian scholars: Lewis, Chesterton, Spurgeon…had he been rooted in reality.

For Tolkien, it was reality that shaped his fantasy work, which in turn brings the reader back to reality. After all, the best make-believe stories can help us make sense of the real world. Is it possible that Tolkien’s fantasy—or “faërie”—world could lead someone to a deeper understanding of Christianity? Tolkien had quite a bit to say about that; but first…

Tolkien’s faith must come from somewhere, right? Indeed, it does.

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born in 1892 in Bloemfontein (Bloem, South Africa today) to British middle-class parents, Arthur Reuel Tolkien, a bank manager, and his wife, Mabel née Suffield. While J.R.R. accompanied his mother and brother Hilary on a family visit to England at age 3, Arthur passed away in South Africa from rheumatic fever, leaving the Tolkien trio without an income. Mabel, along with her sons, moved in with her parents. As a diabetic, two decades before insulin treatment would become available, her condition steadily worsened until she died in 1904, when J.R.R. was 12. Of all the virtues she left behind, her Christian faith was unmistakable.

At age 21, Tolkien wrote of Mabel: “My own dear mother was a martyr indeed, and it is not to everybody that God grants so easy a way to his great gifts as he did to Hilary and myself, giving us a mother who killed herself with labour and trouble to ensure us keeping the faith.”1

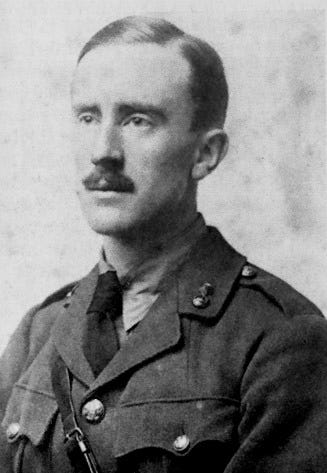

In August 1914, Britain entered World War I. Tolkien enlisted in the British Army in 1915 and served as a second lieutenant signals officer: responsible for communicating from field to headquarters through three main forms, handwritten letters, telephone operations, and carrier pigeons. Then came the horrors of the Battle of the Somme, where the British Army alone had 420,000 casualties (nearly 100,000 fatalities). The bloodshed of fellow young British soldiers struck Tolkien in more ways than one. A horrific bout of trench fever took him out of commission, and for the next two years he petitioned medical boards to re-enter service, only to be deemed medically unfit. He was continuously delayed until a ceasefire was agreed upon in 1918, formally ending the war by the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. For Tolkien, however, the scars of war never truly healed, serving as a poignant reminder of the depravity of the human condition.

The loss of many close friends, mental trauma of trench warfare, the war-machine industrialization of Europe: loss, despair, dread. Welcome to sin’s grip of the human condition. We are all vile, violent, vengeful creatures in need of hope—somewhere, somehow.

Christianity has always provided the answer to the search for hope, one oftentimes discovered in life’s darkest pits. David wrote in Psalm 30: “Hear, Lord, and be merciful to me; Lord, be my help. You turned my wailing into dancing; you removed my sackcloth and clothed me with joy, that my heart may sing your praises and not be silent. Lord my God, I will praise you forever.” Anyone familiar with David understands his lowest pits were where God spoke to his heart the clearest, building his faith in ways that only God can—David is credited in writing half of the Psalms.

For Tolkien, it was no different. As a devout Christian (a Roman Catholic), the pain of life became his heart’s cry to God, a true connection point in his faith. He tethered his devotion to the Lord with his passion for linguistics, resulting in, among other compositions, The Lord of the Rings. Now we return to our question: Was high fantasy writing the best Tolkien could’ve offered this broken world?

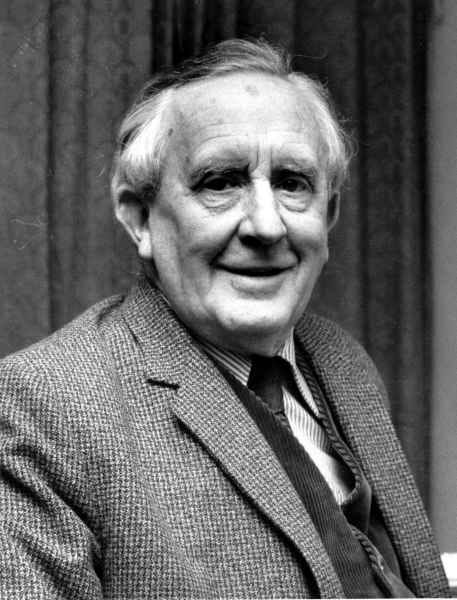

J.R.R. Tolkien was the world’s leading expert on languages during his professorship at the University of Leeds and University of Oxford, specializing on Old and Middle English. His love for language, real and self-created, served as the foundation for Middle-earth. Fantasy, or “faërie”, worlds became his life’s work, much of which was realized posthumously in the piecing together and publishing by his son, Christopher. What we have today is, what many would agree, the greatest high fantasy legendarium ever created. At its simplest form, the stories are escapism; and who could blame him? Do we not all desire, in some capacity, to escape to a “better” place? Paradise? (We’d call it “Heaven”, of course). If God’s Word is true, and the world is not our home, shouldn’t there be an innate desire, a longing to get to where we belong?

Tolkien in “On Fairy-stories” (1947):

“Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it. In using escape this way the critics have chosen the wrong word, and what is more, they are confusing... the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter.”2

Could Tolkien’s Middle-earth be a gateway to Christianity? Absolutely. I am not God. No one can definitively say whether or not Tolkien could’ve been more “Christian” in his written narratives. We must be reminded, however, of the power of story-telling.

Jesus himself was a master teller of stories. He didn’t just preach God’s law and give instruction for how to live holy lives, he presented parables—and what is a parable if not a story? A great story, in and of itself, does far more than simply provide a rising action, climax, falling action, etc. It gives us a lesson; a perspective shift—something to not just hold onto, but rather to unpack, apply, and respond.

As we read the stories of Middle-earth, we begin to make connections to our own place in God’s story. We see the virtues of hobbits, the temptation of the One Ring, the self-sacrifice of Frodo (and to an extent, the Fellowship as a whole); we see the juxtaposition of good versus evil, the influence of higher powers on the outcome of mortal beings; we see the overlooked and underwhelming individual rise above their misfortunes to change the world, how love triumphs over evil, the emphasis of forgiveness—it’s all there. Biblical narratives abound in Tolkien’s work.

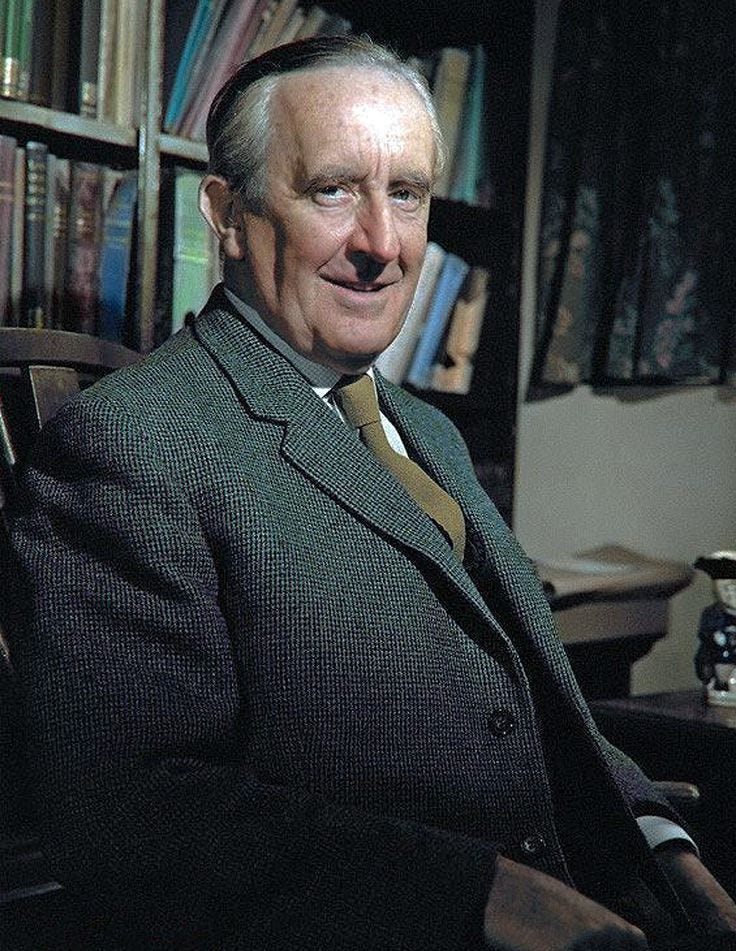

While Tolkien insisted the Lord of the Rings was not allegory (to Christianity or the Great War), he rightly understood his life experiences must be fundamental and foundational to the narratives of Middle-earth. In a letter to his friend Robert Murray in 1953, responding to Murray’s praise of “a strong sense of a positive compatibility with the order of Grace”, and comparison of Galadriel to that of the Virgin Mary, Tolkien responded:

“The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision. That is why I have not put in, or have cut out, practically all references to anything like ‘religion’, to cults or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.”3

In Tolkien’s own words: “The religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.” Can Middle-earth be a gateway to Christianity? Maybe the real test resides in the individual. For me, the answer is unequivocally: "“YES”.

In 1971, a letter by Tolkien contained the following account:

“I had one [a letter] from a man who classified himself as ‘an unbeliever, or at best a man of belatedly and dimly dawning religious feeling…but you’, he said, ‘create a world in which some sort of faith seems to be everywhere without a visible source, like light from an invisible lamp.’”4

Light from an invisible lamp. Middle-earth.

If you enjoyed this article and want to read more like it, I’ll be releasing more content in the coming week.

Tolkien, J. R. R., Flieger, V., & Anderson, D. A. (2008). Tolkien on Fairy-stories. HarperCollins

Carpenter, Humphrey (1977). Tolkien: A Biography. New York: Ballantine Books

Tolkien, J.R.R. (2000). The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien: A Selection. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. 171-172.

Ibid., 413.

“As we read the stories of Middle Earth, we begin to make connections to our own place in God’s story.” Well said. As for me, Middle-earth and Narnia and Prydain were the Great Three which stirred me and drew me towards the Christian gospel. It is very likely I would looked for a New Age mystical alternative if I had not discovered that Jesus Christ is the One whom my pagan heart was really longing for.

ah....in the words of C.S. Lewis "further up and further in"....Narnia touched me like Lord of the Rings touched you. I do love The Hobbit as well....I have an upcoming post I am going to have to link to here....! thank you for sharing your perspective